Toxicity in competitive gaming and role of organized esports

About the study

For the past few years, we have been researching the topic of “toxicity” in competitive gaming. We have done this in cooperation with, and partially funded by, the City of Helsinki Youth Services project Non-toxic –non-discriminatory gaming culture. Here, we put toxicity in quotation marks not because we in anyhow suspect its existence in competitive gaming – we do not and we have seen plenty of evidence to prove otherwise! – but because it often covers quite a wide range of different types of negative behaviour in video games.

These include, for instance, verbal harassment, trashtalk, name calling, throwing (losing games on purpose), different forms of sexism and racism, doxxing (revealing someone’s real life identity or information related to it), competitive rage, and trolling. All these are part of the toxic landscape of competitive gaming, but when we are researching it, differentiating between different types of behaviours can be helpful. It can help us to better understand the different motives behind these behaviours as well as their possibly structural nature (more about that soon!).

“Likewise, differentiating between different types of behaviour can also be extremely helpful when looking for solutions for toxicity.”

While conducting our interview study of young players’ (16-27 years old) own toxic behaviour, it became evident that not only types of negative behaviour vary, but also their intensity (Ruotsalainen & Meriläinen, 2024). Playing games competitively can often be quite an intense affair and players’ emotions can run hot. This can amount to emotional outburst, often directed towards one’s teammates, but also towards enemy team members, gaming accessories (such as controllers and screens), and yes, even towards one’s own mother. After the intensive emotions pass, the players can then deeply regret what they have said or how they have acted.

Our study participants also shared with us different ways they have learned to cope with intensive emotion while gaming, for example by taking a break to cool down or muting themselves and yelling at the screen instead of other players. Indeed, in our paper we suggest that one of the ways to address toxicity in play is for players to develop emotional, social, and communicative skills (Ruotsalainen & Meriläinen, 2024). It is also important to note that in our study the perpetrators of hostile behaviour were also often its victims and vice versa.

Banal toxicity

However, it is clear that it is not all about intense emotions and quick outbursts followed by regret, solved by everyone becoming a little bit more zen. As our other study (Meriläinen & Ruotsalainen, 2024) aptly demonstrates, the issues are also deeply structural and normative. For this study, we collected open answers from 95 young people about their experiences of their own toxicity while playing video games. What our results showed was that not all toxic or hostile behaviour is sparked by intense emotions, but oftentimes it is “just because”: players act in a toxic way as that is the way they have learned to act (and expect everyone else to act) while gaming.

Due to the normalised and everyday nature of this type of behaviour, we named it banal toxicity. We want to stress that this banality or everydayness by no means equates to harmless – on the contrary, banal toxicity and for example the slurs that are part of it can be just as harmful to its recipients as more emotionally intensive toxicity. The groups that are in a vulnerable position in gaming are at particular risk, as slurs are often racist, sexist or transphobic in nature. In this way, banal toxicity normalises and reinforces structural inequalities.

Banal toxicity shows how hostile behaviour has become the norm in many game spaces and that to tackle toxicity it is not enough to focus on individual players, but we need practices and design solutions that tackle the normative structures of competitive play. Here, different kinds of organised activity around esports can be helpful, as they can challenge existing norms and tackle the banal toxicity in competitive play. This is especially important in organised esports for young people: competitive does not have to mean toxic or hostile, but it can be communal and supportive.

Changing game cultural norms is often an uphill battle, but working together is much more fruitful than working alone. This also means that it is important to tackle the everyday toxicity in esports, rather than seeing it as something necessary or harmless or as natural part of it. Everyday conduct contributes to the wider structural issues also in a positive sense, and organised esports can be a great space to learn emotional coping skills and social and communicative skills – as long as it keeps its banal toxicity in check!

Authors:

- Maria Ruotsalainen, University of Jyväskylä

- Mikko Meriläinen, Tampere University

References

Meriläinen, M., & Ruotsalainen, M. (2024). Online disinhibition, normative hostility, and banal toxicity: Young people’s negative online gaming conduct. Social Media+ Society, 10(3), 20563051241274669.

Ruotsalainen, M., & Meriläinen, M. (2023). Young video game players’ self-identified toxic gaming behaviour: An interview study. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, 14(1), 147-173.

READ MORE

Jamk launches new gametech and esports project initiatives

Jamk University of Applied Sciences is launching three new game and esports related RDI projects in Central Finland.

The study investigates the effects of physical warm-up on aiming accuracy in FPS games

In spring 2025, research measurements will be conducted at GamePit Pro to analyze how different forms of physical warm-up impact aiming performance in FPS games, using the data collected.

Ideas for e-football from the InnoFlash course

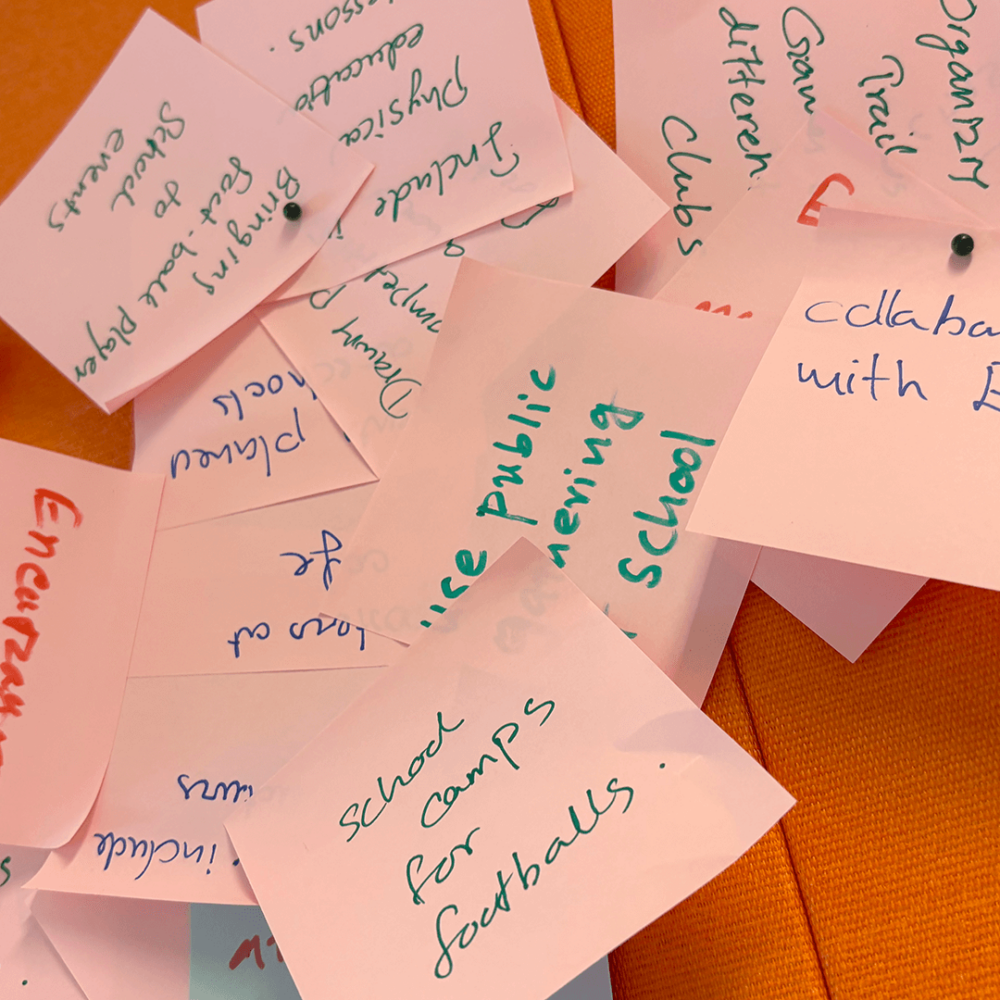

The InnoFlash week gathered Jamk students for an esports-themed assignment. Eight teams prepared a total of 24 concepts aimed at engaging new interested members to join football clubs through e-football.

Stage142 returns to Jamk in April!

Stage142, will gather the LAN crowd to Jamk main campus once again from April 4th to 6th! The event is organized by Jyväskylä Esport Association.